Eye Witness

Testimonies

Newspaper

Archives

Greek MFA

Telegrams

Political

Background

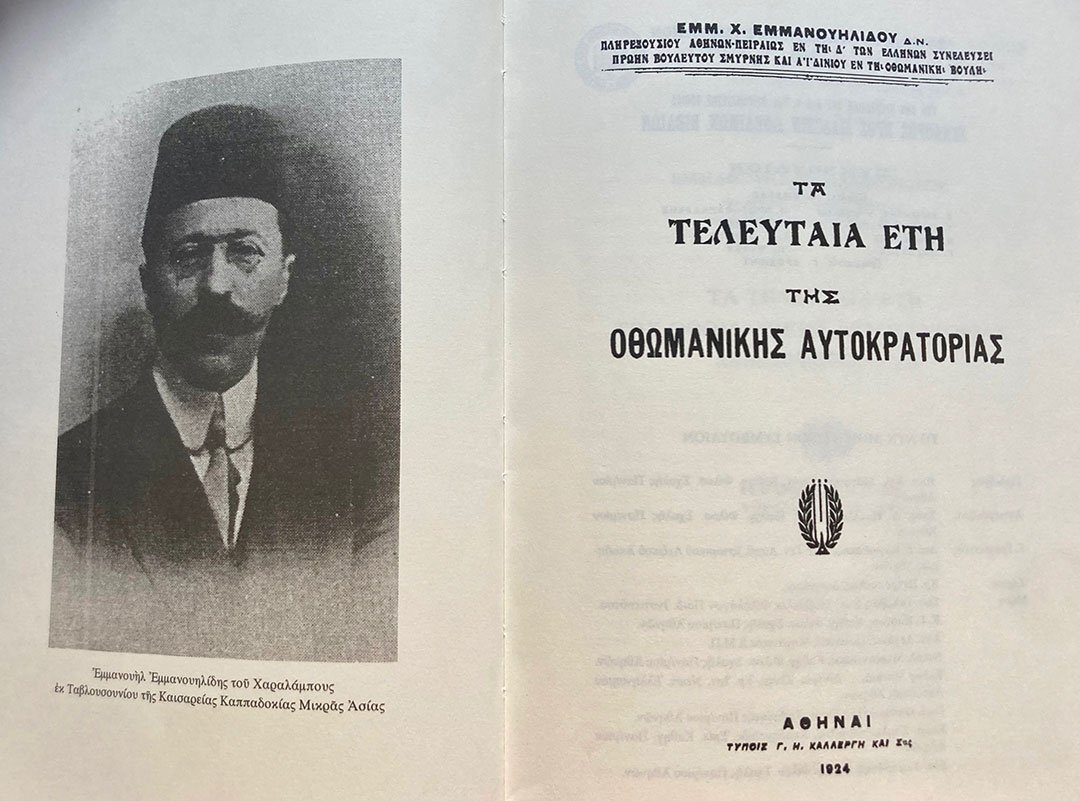

| Emmanuil Emmanuelidis | EN | GR |

THE FINAL YEARS OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

by EMM. CH. EMMANUELIDI

Member of the Ottoman Parliament for Smyrna and Aydın

Published in Athens, 1924

THE FIRST GREEK PERSECUTIONS

The first thrust was directed against the Greek element who, in their view, was to be blamed for the Balkan war and the Muslim migrations from the lost provinces.

The commercial boycotts began shortly after the rise of the Young Turks to power and was quickly extended to all Greek lands and took on an unprecedented intensity during the first months of 1914.

In the name of the Prophet and the homeland, the boycott was advocated through mosques, clubs, and journalistic columns. No Muslim was allowed to do business with a Greek; if he did, he was obliged to dissolve the deed; if he refused, he was mercilessly beaten and the object of the sale was destroyed. This law was called “National Will” (Milli İrade), and its justification was the National Awakening. Armenians and Jews were subject to the same obligations, otherwise they were also boycotted. The mufti of Kırkağaç, who issued a fatwa against the boycott, because it was opposed to the Holy Law, was summarily dismissed of his duties. There was a special committee in each area, supported by a group of bat-bearing thugs, who were to carry out its decisions; the committee issued, for a certain fee, a sealed permit for any goods that were not to be subjected to boycott. No law, of course, prevented the wronged ones from making a similar seal, and this measure was widely used in Smyrna. But despite what could or could not be done in Constantinople and Smyrna –because in these two cities, at first at least, these measures were ridiculed– these measures caused other Greek communities enormous harm, especially in the interior of the country. The Greeks, struggling between being mistreated by the Government and being antagonised by the Levantines –who were multiply supported from outside the country– owed their prosperity solely to their ability to make their small capital profitable through daily work. But the Young Turks had forbade this work, then and for the future. As for the Greeks’ rivals, they were taking advantage of the situation with schadenfreude. In the meantime, sealed envelopes were being distributed to the muhtars, which were not to be opened under penalty of death until there came specific orders by the War Ministry. There were a lot of rumours circulating in Smyrna, and no one dared to guess what would happen from one day to the next.

During the spring of 1914, paradoxical events unfolded, first in Eastern Thrace. In those parts, which had suffered the calamities of the Balkan War, evil began when the peace negotiations in London were interrupted. Inhabitants started being arrested, beaten, and thrown into prison by military courts; murder and rape was of the daily order; the Christian villages became occupied by the Army and it became unsafe to stay and work in the fields. During the first two months of 1913, Krithea [Alçıtepe] was evacuated and looted; Plagiarion [Bolayir] was also looted. In November of the same year the houses and shops in Neochorion [Yeniköy], Vairion [Bayırköy], Galata [Sütlüce], and Gallipoli [Gelibolu] were evacuated, and the goods were thrown in the streets; “go throw yourselves in the water” was the replies received by the desperate Christians. […]

During the Balkan War, the retreating volunteer battalions and the Muslim refugees had already looted the villages of the Didymoteicho region. […] Elmalı near Malkara, Mahmutköy, and Gravouna [Grabuna] were set on fire; the Christian district of Kessani [Keşan] suffered the same fate. […] Of course, individual killings or massacres accompanied such disasters. Irregulars who disembarked on January 26, 1913 by warship in Ekonomio [Kumburgaz] slaughtered most of the men; when the regular army arrived, it attacked the women. […]

Aka Gündüz, the Turkish poet we mentioned earlier, used to boast that he was Attila’s descendant. Indeed, the recapturing of Thrace by the Turkish army at the end of the Second Balkan War resembled a true invasion by the Huns. Irregulars and regulars, soldiers and refugees, they scattered througouht the country, destroying, setting fire, killing. […] The women again became victims of vile appetites; a virgin, to avoid disgrace, was thrown out of the window; they raped the quivering corpse. Eighty-year-olds were defiled, seventy-year-olds were disrespected. Animals were stolen, children were taken away. They stole everything they could find and when the residents were left with nothing, they blackmailed them to sign debt notes.

[…]

When the Turks recaptured Thrace, the Greeks were considered to be the perpetrators of Bulgarian atrocities and were obliged to rebuild all ruined buildings through their own labour and expenses.

Anyone who declared himself a Muslim with lost property, was entitled to compensation, taken from the property of the Christians. […] Accusations against Christians were decided administratively, but even if referred to court, every Muslim considered it his duty to contribute to their conviction, even by false testimony.

Deaths of Christians took place in various places. Insults and whippings were the rather cursory results of trials.

[…]

Men ages 19 to 30 years of age were called to arms; conscripts were sent without clothes or food to build Muslim villages or engage in other forced labour. Only 10% of the defendants were able to pay the required fee for exemption.

Under this administration, the Greeks, excluded from all work, unable to go out into the fields, attacked by thugs in cities, villages, and even at home, overwhelmed by hundreds and thousands of fanatical and hungry refugees, robbed by robbers and citizens alike, from natives and foreigners, from individuals and officials, understood that there would no longer be a humane life for them in that country, which, even though it had always been Greek up until then, the Turks now wanted to turn it Turkish.

At this psychological moment the gangs appeared. A breath of barbarism passed through the country again; murders, attacks, night shootings, disturbances of houses, neighbourhoods and villages. Desperate, the Christians started evacuating their lands, and the authorities, dropping their mask, ordered the full evacuation of Christian villages under the pretext that the Government could not keep the order.

That’s how the Greeks of Thrace were expelled to Greece in 1914.

The very same means, the very same plans, the very same thoughts caused the very same results in Asia Minor. The difference was that there, everything was more systematically organized, because within the empire –where so many European interests were exposed– speed was considered of imperative importance.

Here, too, there had been persecutions, arrests, arrests and especially boycotts. 1913 was a year of restlessness; 1914 arrived with worse omens. The boycotts were in full swing that year. Suddenly, through a combination of rapid and synchronised action among the administration, the police, the gendarmerie, organized gangs, local Muslims, and immigrants from Serbian Macedonia, Western Asia Minor, and especially the Izmir region itself, was thrown into complete turmoil within a month or two (May-June ). Eritrea [Karaburun], the islands of the Smyrna gulf, the coast of Phocaea, and the area of Bergama were deserted. In total panic, the Greeks of said areas left their homes and property behind, fleeing, naked and deprived of everything, to the beaches, begging for ships to take them for refuge in Greece. The events took the form of true massacres in Seyreköy, Phocaea, and Eglezonisi [Uzunada].

The uproar caused by the “Smyrnaika” events [the events of Smyrna], frightened the Ottoman government. Talaat, then Minister of Internal Affairs, went to Smyrna to quell the unrest. What he did was to complete, of course, the destruction and to return and report to Parliament the measures he had taken in order to restore order. The events, he said, were the result of the influx, in those parts, of hundreds of thousands of Macedonian Muslims, who had been forced to emigrate.

Parliamentary Exchange

Listen to what transpired in the Ottoman Parliament on 18 June (1 July) 1914, as the Ottoman Greek MPs –esp. Em. Emmanuelidi– called upon Talaat Pasha to explain himself and the persecutions in Phocaea and other coastal areas.

[The exchange is translated from the Ottoman Turkish and found in Dr. Emre Erol’s book “The Ottoman Crisis in Western Anatolia”]

Celâl Bayar

Celâl Bayar was at the time the Izmir leader of the governing Committee of Union and Progress party. Much later, he became the 3rd President of the Republic of Turkey.

Celâl Bayar was at the time the Izmir leader of the governing Committee of Union and Progress party. Much later, he became the 3rd President of the Republic of Turkey.

Eşref Kuşçubaşı

Eşref Kuşçubası was a top-ranking member of the C.U.P.’s paramilitary organisation Teşkilat-i Mahsûsa, and the man behind many reconnaissance operations in Western Anatolia/Asia Minor

Eşref Kuşçubası was a top-ranking member of the C.U.P.’s paramilitary organisation Teşkilat-i Mahsûsa, and the man behind many reconnaissance operations in Western Anatolia/Asia Minor

Emmanuil Emmanuelidis

Emmanuil Emmanuelidis was the Member of Parliament for the province of Aydın (where Phocaea and Smyrna belonged). He was an Ottoman Greek, elected with the C.U.P.

Emmanuil Emmanuelidis was the Member of Parliament for the province of Aydın (where Phocaea and Smyrna belonged). He was an Ottoman Greek, elected with the C.U.P.

Talaat Pasha

Talaat Pasha was the Minister of Internal Affairs from 1913 until the end of WWI. Together with Enver and Cemal pashas, He was one of the “Three Pashas”, the triumverate that essentially ruled the Ottoman Empire at the time.

Talaat Pasha was the Minister of Internal Affairs from 1913 until the end of WWI. Together with Enver and Cemal pashas, He was one of the “Three Pashas”, the triumverate that essentially ruled the Ottoman Empire at the time.